What I Saw Around The Curve

Notes from the near-future of AI

After The Curve, Eli Pariser wrote an extensive account of things he learned at the conference. Full of insights, it’s a fascinating glimpse into the conversations that arise when a few hundred insiders from across the AI landscape get together. He gave permission for us to share it with you.

Eli is author of The Filter Bubble and Co-Director at New_ Public, a nonprofit product studio focused on reimagining community, connection, and conversation online. You can follow their biweekly newsletter here: newpublic.substack.com.

Coming up next, I’ll be posting A Project is Not a Sequence of Tasks (working title) – some musings on the path to full automation of software engineering, drawing on my own 40-year career writing code.

And now, over to Eli!

What I saw around The Curve

I attended The Curve, a conference of ~350 top AI lab leaders and scientists, safety activists and alarmists, political advisors and lobbyists, journalists, and civil society leaders. The event took place in Lighthaven, a quirky cluster of houses in Berkeley that have been retrofitted into small conference spaces. Many sessions were in living room-sized spaces, so it was all very personable and informal — an impressive feat by the organizing team.

The vibe: Convivial, affable, and slightly doomy

Many participants seemed thrilled, awed, and also deeply worried. Someone described it as “snorting pure San Francisco.” At 45 I was one of the older participants — the average age was mid-30s, but many of the most powerful people were in their late 20s. Pretty much every single person I talked to was smart, relatively humble, and pleasant. You couldn’t throw a rock without hitting someone with a large Substack following.

(Some sessions were on the record, some off, thus the vague sourcing in some places below.)

“It will accelerate”

There was broad consensus that the pace of progress in AI models will continue to accelerate, though lots of debate about how quickly. A senior lab official said that 90% of the code in one of the frontier labs is now written by AI models (!!), and that they’re already replacing some entry-level technical jobs with automated agents.

(Another person told me that this was a bit of a canard — these are fairly rigid, well-specified jobs and the labs obviously have the most expertise in how to fine-tune models to meet their own specific needs — so they have an unrealistic sense of how hard it will be to apply AI this extensively outside their own walls.)

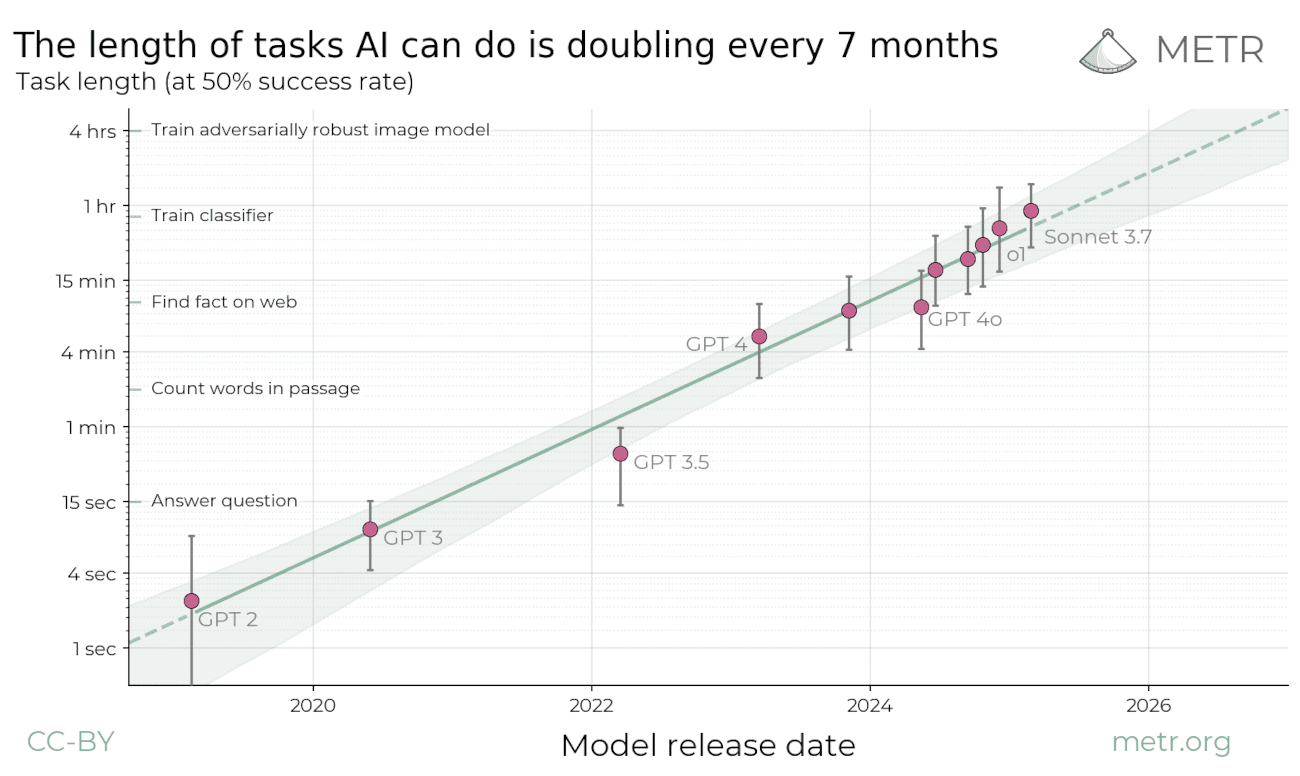

An official from another lab pointed out that the scope of tasks chatbots can handle autonomously keeps rising1:

There was a general sense that “recursive self-improvement,” where labs build automated AI researchers that develop better AI models that build better researchers, is still some time away — possibly just a few years, possibly much longer.

The general lab belief here (which is a bit maximalist), as one person described it, is that there are no barriers on the path to true human-level general intelligence (AGI):

“Capabilities based on current methods will continue to improve smoothly”

“New methods will continue to arrive and accelerate progress”

“Compute development will accelerate and compute bottlenecks will be overcome”

“Normal technologists” and those worried about accelerating existential risk agree that it’s likely there will be rapid near-term acceleration

One of the big debates in AI is whether this is a “normal technology” — whose progress will be subject to friction and delay as it is adopted by human social systems — or it’s going to start improving itself exponentially and “take off”. Generally the “takeoff” people don’t think this will end well2.

There was a great session where one of the originators of the Normal Technology hypothesis (Sayash Kapoor) and the lead author of the AI 2027 paper talked about what they agree on. There was broad agreement from both that, in the short term, AI may advance rapidly:

The size of coding tasks which AI systems can carry out independently may quadruple within a year

Revenue in 2026 will continue to grow exponentially — perhaps reaching $60-70B / year

They did not agree on recursive self-improvement, however — the Normal Technology team thinks that’s a long way off, if it ever happens. Both sides generally agreed that there’s a big gulf between rapid progress in a lab and deployment in the real world.

My sense is that Normal Technologists anticipate the speed of change to be substantially higher than people who aren’t following AI closely — and that the Normal Technology view is often misunderstood as predicting slower progress than its authors actually expect.

But… the frontier may remain “jagged”

AI policy leader Helen Toner gave a great talk pointing out that right now, AI capability is “jagged” — just because LLMs can do some things doesn’t mean that they can perform other tasks of seemingly equal difficulty.

She suggested that this may be a permanent state of affairs, because:

It is easier to check whether an AI’s work is correct for some tasks than others

For many tasks it’s difficult to encapsulate all of the necessary context in a way that’s accessible to a chatbot

The level of adversariality of tasks will differ, and working against adversaries is a different kind of problem

Some tasks that seem cognitive will continue to require embodiment (Toner used the example of deciding on an event venue).

Different combinations of capacities have different implications for who benefits, who loses, who has power, and who is provoked

The emerging politics are very weird

On the one hand, there’s a relatively bipartisan elite consensus.

The general sense was that there’s considerable continuity between Biden and Trump AI policies. There was a session between high-level Biden and Trump AI advisors that I didn’t see much of, but it was described as largely aligned and convivial.

Rep. Sam Liccardo, Congressman from the San Francisco Peninsula, who was interviewed at the conference, said he expected some kind of federal preemption to pass — that colleagues in tough races probably wouldn’t vote for it, but everyone else will. He described elite political opinion as being focused on a mix of China, jobs, cybersecurity, and bioterrorism.

On the other hand, there’s a kind of cross-partisan populist angst.

The most packed session of the entire conference was Taren Stinebrickner-Kauffman interviewing Joe Allen, a Steve Bannon-aligned figure who is strongly anti-transhumanist3, anti-surveillance, and largely anti-AI from a somewhat apocalyptic Christian point of view.

Meanwhile, union leaders, who are already very skeptical about AI, are getting pushback from rank-and-file members for engaging with AI or AI labs at all. And more broadly, Americans across the political spectrum seem to clock that this is unlikely to be good for them or their jobs.

It also seemed clear that there’s going to be a lot of money spent in a battle between AI safety and AI accelerationist forces. Many of the newly minted centimillionaires and billionaires of the AI age are deeply concerned about runaway AI creating catastrophic risks and are pouring large sums into safety efforts. In contrast, Marc Andreessen, OpenAI President Greg Brockman, and others are launching a $100M pro-AI, anti-regulation Super PAC. It sure looks like this is going to make the wars over crypto look like a drop in the bucket.

In this context, it was interesting to note that while concerns about work and job displacement are a major part of the mix, there’s a lot of energy around regulating how predatory chatbots interact with children. The organizer of a right-leaning AI safety organization told me she had tested a wide range of messages. Worries about sexually predatory chatbots forming relationships with kids, as well as driving them to suicide, were by far the most energizing.

I also attended a session by the Future of Life Institute’s Hamza Chaudhry, who is thinking very seriously about how chatbots will be weaponized to infiltrate, persuade, and create threats to national security infrastructure.

The labs think they will be toxic soon

There was general agreement among many people both inside and outside the labs that they’re likely to be broadly hated — as much as, if not more than, social media companies are today.

Anthropic is clearly trying to position itself as “the good one.” Its business model is focused more on code-writing and revenue from enterprise customers, which they see as shielding them from some of the worst consumer pressures. They tend to style themselves as a kind of “rebel alliance.”

There was also a lot of embarrassment, from people both inside and outside OpenAI, about Sora 2 and the general sense that they’re slipping into doing “stupid addictive social media stuff.”

US versus China is very much a thing — but we may have China’s strategy wrong

Generally, the labs all believe they are defenders of democracy — and of “democratic AI” — against China. This was a very lively conversation and a major motivator for acceleration among U.S. AI experts, especially around national defense and cybersecurity.

Rep. Liccardo’s position: If we lose this race, China writes the rules.

However, there was an undercurrent of concern that we may be reading China’s AI strategy wrong. One participant told me that the vast majority of China’s efforts are focused on “embodied AI” — i.e. robots — because that’s where the most pragmatic economic growth opportunities are. It’s not at all clear that China’s industrial policy around AI is aimed at developing super-intelligence.

There was also discussion of how China is positioning itself as anti-imperial-America in Africa and other regions, offering support to build sovereign AI systems and models.

Computing capacity seems likely to remain a chokepoint in the near future

There was general agreement that access to data centers is going to be a key source of AI power — not just because that’s how new models are built, but because it’s what’s needed to run them at scale.

An OpenAI official described how “inference-time compute” is scaling intelligence — meaning that if you throw more processing power at a model to let it “think” longer, you get dramatically better results.

In other words, if you want to slow down development and use of AI, you either have to slow down the supply of AI chips or slow down the energy they need.

There’s a lot of uncertainty about when and how job displacement might hit

It was a majority opinion that entry-level jobs are already being displaced. One of the authors of a well-known paper on this, Canaries in the Coal Mine, was in attendance. He’s finding that there’s a reduction of employment in entry-level jobs specifically in fields predicted to be exposed to AI automation.

There was also fairly broad consensus that there will be significant disruptions in jobs over the next 3-5 years — but with big error bars. Even the AI 2027 team was not confident that AI would contribute 1% of GDP by 2028.

An anecdote that’s often used in this vein is that there are actually more bank tellers now than there were in 1980, when ATMs rolled out. But, as Mike Kubzansky from Omidyar pointed out, that story is incomplete — it was true up until 2008, when mobile banking rolled out. After that, the numbers collapsed.

Some interesting ideas about how AI might aid democracy

There was an insightful panel on how AI might support a healthier democracy.

One idea focused on digital human rights shields — one of the big labs worked with human rights lawyers in the Philippines, where 50% of staff face murder threats, to create an early warning system that detects chains of events leading to killings, successfully protecting targeted individuals.

Another example was anti-corruption tech in Ukraine, where AI tools are used for direct government contracting that is “disintermediated” from corrupt practices, saving millions and creating public trust while reducing opportunities for foreign influence.

A third idea involved public health data — with the erosion of federal public health infrastructure, AI tools can provide high-quality medical data, precedents, and playbooks for local and state agencies dealing with health crises or outbreaks.

We’re in the early days of AI privacy, security, and influence concerns

A number of researchers I spoke with described how challenging it will be to have AI systems engaging with other systems without revealing private information from their owners. It’s not that hard to get AIs either to explicitly share this information — or to accidentally reveal what they “know.”

There were similar worries around security and influence. A security expert pointed out that even novice hackers — still affectionately known as “script kiddies,” a term coined in the 1990s — now have expert-level AI assistance to write scripts and make trouble. This allows for much more sophisticated attacks to be launched by much less sophisticated actors.

A researcher studying foreign influence operations said essentially the same thing: with minimal resources, no human agents, and limited language or technical capacity, it’s now possible to run a fairly sophisticated influence campaign.

“Cognitive shields” seem like a good idea, but not something anyone’s working on per se

I floated an idea that my old friend and mentor Wes Boyd has been raising: using AI to shield against manipulation and influence. You could imagine having a personal AI that’s accountable to your more aspirational self — one that nudges you away from harmful distractions and toward wellbeing and growth-oriented activities. There was generally a lot of interest and appreciation for this idea among the people I raised it with, but no one seemed to be actively working on anything like it yet.

Sycophancy was a big topic — and might be an artifact of human reinforcement learning

The tendency of chatbots to tell people what they want to hear was a big topic.

This was already on my mind because of a recent study showing that people generally not only prefer sycophantic chatbots but often see them as less biased — and that only people who score high on “openness” psychologically prefer chatbots that disagree with them.

There’s some interesting speculation that chatbots’ tendency towards sycophancy is the result of human feedback gone awry. When people rate chatbot responses with a thumbs up, it’s often because they like what they’re hearing, not because it’s correct. How to solve this is complicated.

Some interesting future provocations from people at the labs

A few talks I attended featured people from the big commercial AI labs speculating about what this all means for society, politics, and beyond. I found many of the ideas interesting — but also ungrounded in any general sense of social dynamics, politics, or history. That said, here are a few that stood out:

“We’re moving from an attention economy to an attachment economy.” Peak attention has come and gone; now we’re moving to attachment as the scarce resource.

Something that looks like gaming will increasingly replace what we now think of as work.

All types of relationships with AI will be normalized, including spiritual, romantic, and sexual relationships. Some people will want to give AI personas personhood and maybe even rights, while others will strongly oppose this.

People will slice, dice, license and monetize their identities in a whole series of new ways (this is something I buy for sure.) They will create a digital “twin” of their consciousness and replicate it.

There’s a coming fight between transhumanists and humanists/“mortalists” — those who want to merge with technology and pursue immortality versus those who remain rooted in embodied humanity. This will likely take on political and geopolitical dimensions.

The AI agent economy — with agents taking on increasingly complex, autonomous tasks and making money — will induce “endgame financialization.”

Access to computing power and AI models will become essential and even existential for nations.

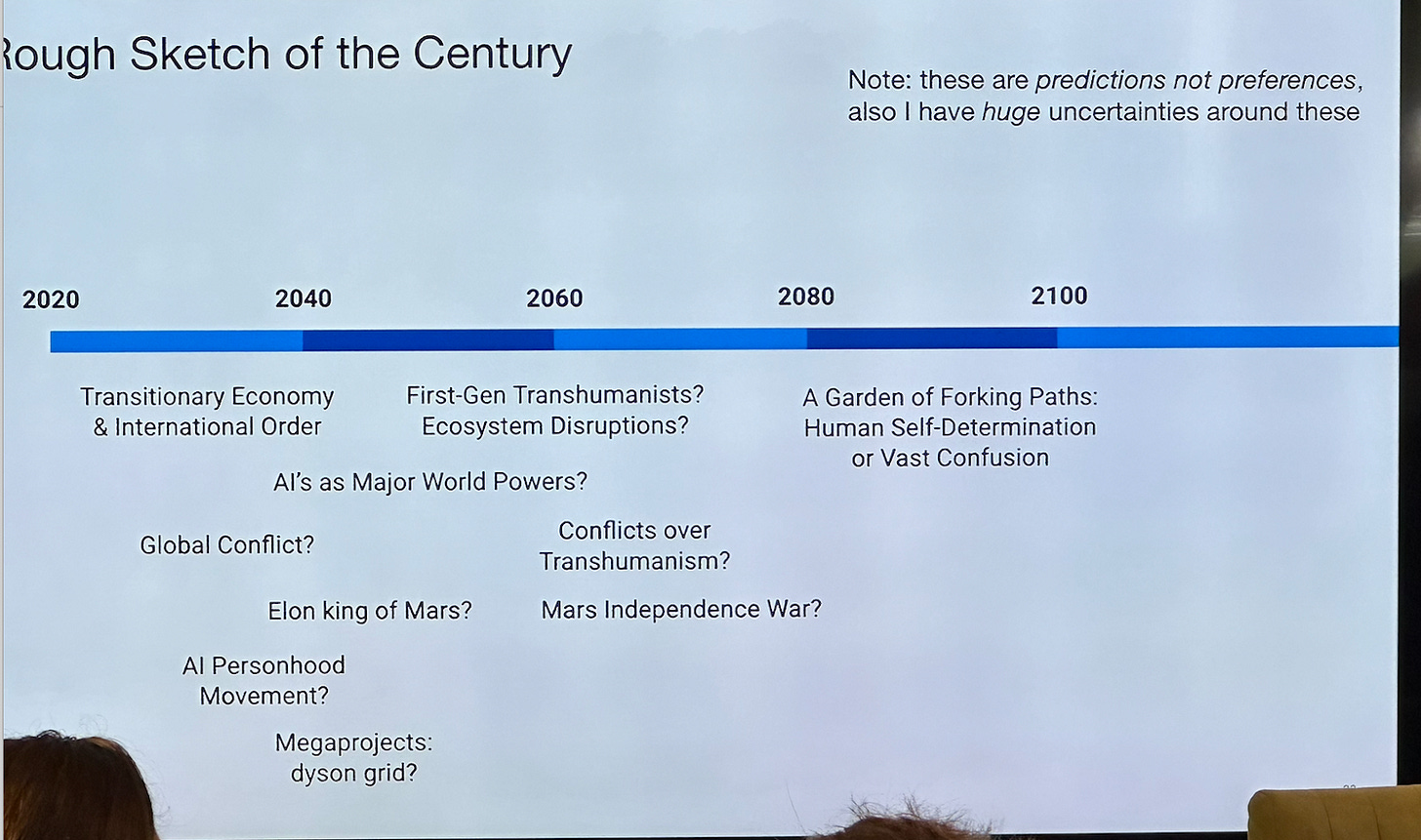

One especially vivid talk came from Josh Achiam, Head of Mission Alignment at OpenAI, who offered a rough sketch of the next century:

A big theme: Determinism vs. non-determinism

Many of the most intense AI safety voices seemed to have a pretty deterministic view of the world. One person speculated that this is because they tend to come out of the AI/ML world itself where math and physics are primary disciplines. As Helen Toner pointed out, they tend to make linear or exponential predictions about the future.

One of the most interesting sessions I watched was a debate between Buck Shlegeris, an AI safety advocate who seemed pretty alarmed about the potential for catastrophic risk — and journalist Timothy B. Lee. Tim patiently and compellingly poked holes in the premise that intelligence alone is sufficient for a super-intelligence to take over the world, arguing that because the world is chaotic and nonlinear, it’s not that easy — especially since there will be other, perhaps slightly less intelligent but still vigilant AIs looking to stop them from doing whatever they’re doing.

There was a strong non-deterministic crew at the conference as well — Toner and some of the people from the big labs who think the world is more like fluid dynamics — impossible to perfectly (or often even imperfectly) predict. I find myself much more sympathetic to this way of looking at things.

My grand unified theory: Focus on aligning AI societies over AI models

AI researchers spend a lot of time thinking about the “alignment problem” — essentially, how do we get AI models to do what we want in ways that are not harmful? A huge amount of the labs’ focus is on this question.

Over the course of the conference I came to feel that this was the wrong way of looking at things.

In part, that’s because I think what we’re headed toward in the near term is a world of billions or trillions of different models with their own goals, context, and learning abilities, bumping up against each other, coordinating, collaborating, and fighting with each other. That will create complexity and emergent behavior, just like every other system with billions or trillions of actors. It looks more like a society — or a biological ecosystem — than a singular “mind” to shape.

In that context, I don’t think aligning individual models is the most important thing. It’s sort of like making a society good or producing wellbeing by making each individual good. That fails because “good” is situational (“Thou shalt not kill” is a good guideline, but not always applicable), and situations are shaped by the dynamics of other actors.

So, yes, moral education is important, but in a society you also want to think about teachers, social workers, police forces, markets, and governance to help regulate behavior and solve problems.

I suspect the same thing is true of the society of agents we’re walking into — the best way to advance the benefits and reduce the harms of an AI-agent-driven world might be to focus on deploying these kinds of capacities, rather than just focusing on alignment of the individual agents.

I’ll admit that this is me taking the frame I like (socio-political) and applying it to this field. But I bounced the idea off a wide variety of people inside and outside AI alignment and AI safety and generally feel like there’s some validity and merit to it.

A need for spiritual voices

Rep. Liccardo, among many others, pointed out that at the end of the day, many of the questions all of this raises are spiritual — and that we’ll need spiritual voices to make sense of it. I think that’s part of why Joe Allen resonated so much — he was speaking in a moral and spiritual tone that few others did.

The wildest business ever made

In the closing session, Anthropic co-founder Jack Clark (who is a wry, likable and humble-seeming British guy) described the situation (possibly with the help of Claude) as being like a kid who wakes up in the night fearing that dark shapes are monsters, turns on the lights… and they are indeed monsters. He said he was afraid of what was coming from scheming, self-improving models, and made a call for “keeping the lights on.”

The first question after he spoke was, reasonably, “if you’re so afraid, why are you building this company and these monsters.”

Clark basically responded that Anthropic believes it needs to force the kind of regulatory mandates necessary to keep this on the rails through transparency. If they can understand the dangers on the frontier and convey them transparently, they can wake up both political leaders and the public to the dangers ahead so we can avert them.

He also acknowledged that the company was nearing the point where this would create deep corporate tension between this mission and its continued existence, because some of the harms they might expose might also expose them to lawsuits and legal risk. He lightly floated the idea of having some kind of liability shield for doing this kind of work — essentially, self-whistleblowing protection.

I was left feeling that Clark and the other Anthropic attendees seem very sincere and concerned. But also, this is literally one of the wildest ideas I’ve ever heard. It’s sort of like being worried about oil’s impact on climate change, and therefore starting Shell Oil to compete with Exxon but also be transparent about its harms so that all oil companies get regulated. And by the way, you have to raise something in the vicinity of ONE HUNDRED BILLION DOLLARS to do that, and to do THAT you have to build one of the biggest and fastest-growing businesses ever created (which they are well on their way to doing.)

I do think there’s merit to the premise that it’s important for an ethically driven company to be in the game. My big question here is around the $100B you need to accomplish this. That amount of capital generally gets what it wants from a business it is invested in.

Anthropic has led research showing how Claude “hides” thinking when it’s being tested in order to “scheme.” This is evidence of “misalignment.” In some ways it seems like Jack and Dario are the ones scheming against their own reward function — and I hope they succeed in that.

Thanks again to Eli Pariser for this fascinating peek at The Curve, and I’ll see you again soon! Remember to check out New_ Public’s newsletter at newpublic.substack.com.

Editor’s note: This refers to a study that we reported on previously here at Second Thoughts.

Editor’s note: see Lab vs. Life: Dissecting “AI as Normal Technology” and When Decades Become Days: Dissecting AI 2027 for discussion of these two views.

Per Google’s AI Overview:

Transhumanism is a philosophical and intellectual movement that advocates using technology and science to fundamentally enhance the human condition and overcome biological limitations. It seeks to improve human cognitive and physical abilities, extend lifespans, and even conquer aging and disease through advancements like biotechnology, artificial intelligence, and nanotechnology. Ultimately, it envisions evolving beyond the natural human form to achieve a “better than well” state, though the specifics and ethics are subjects of much debate.

I thought this was great, thanks for writing it up.

Very interesting write-up. Thanks for sharing all this!