Discarding the Shaft-and-Belt Model of Software Development

AI enables – and benefits from – a move from mega-projects to artisanal solutions

It’s often been observed that taking full advantage of AI will require changing work practices, just as taking full advantage of electric motors in manufacturing required changing the way factories were laid out. But what will those changes look like? Early answers are starting to emerge, coming (unsurprisingly) from the field of software development. Interestingly, the biggest impacts may not be cost savings!

My timeline is suddenly awash in engineers (including me!) reporting that Claude Code is revolutionizing their work. I can see the outlines of a new approach to software development, suited for the AI age. The implications may apply to other fields as well. The key ideas:

AIs struggle (for now) with large projects, but they can drive the cost of small projects to near zero.

This creates opportunities to replace mass-market software (mega projects) with bespoke applications tailored to the needs of an individual or team.

These smaller projects make “vibe coding” feasible – AIs can write and review all the code, and people just need to tell the AI what to do.

To appreciate how a new technology forces us to re-imagine the way we do things, let’s review the story of manufacturing at the dawn of the electric age.

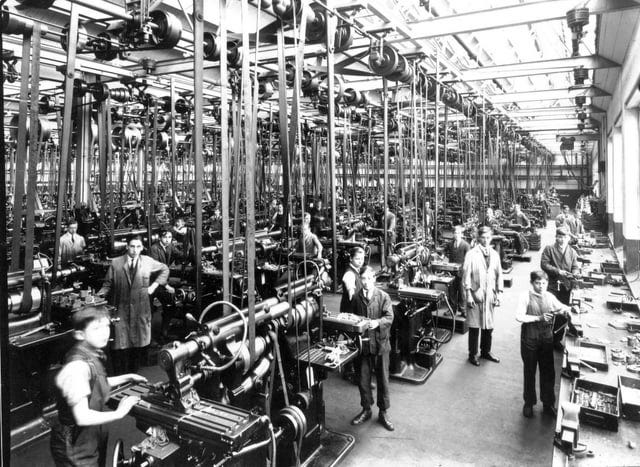

What Factories Looked Like In the Steam Era

19th century factory layouts, designed around the strengths and limitations of the steam engine, would seem ridiculous today. Factories were multi-story buildings, despite the fact that this increased construction costs and required materials to be hoisted between floors. They were festooned with hundreds of leather belts strung from pulleys. These belts were driven by long rotating shafts, which in turn were connected to a single large steam engine in its own attached building.

This awkward system was dictated by the fact that each factory could only afford one engine. Steam engines were complex, expensive machines, requiring constant attention. As a result, every power loom, lathe, or press had to receive power from a single engine. The shaft-and-belt system could not transmit power over long distances, precluding a single large floor, so factories had to be stacked into multiple smaller floors1.

Small steam engines were not practical, but small electric motors were – they were cheap and low-maintenance. As a result, each machine could have its own motor. This eliminated the need for shafts and belts; power was transmitted over wires. Wires could run for a long distance, enabling flexible arrangements and allowing the factory to be laid out in a single floor.

In this analogy, software engineering is still mired in the steam era. Designed around the strengths and limitations of human engineers, current development practices will soon seem as ridiculous as a factory full of shafts and belts.

Software Development In the Hand-Coding Era

We build giant one-size-fits-all applications, despite the fact that most users only use a small fraction of the feature set. (I’ve been an intensive Notion user for years, and I only ever touch 3 of the 20 items in its main menu.) These complex applications demand large engineering teams, whose work is difficult to coordinate. A single application may have millions of users, requiring complex backend systems. Multiple layers of customer support agents and product managers separate users from developers. Changes must be rolled out carefully, and elaborate measures are needed to minimize downtime. Rebuilding an application from scratch is too enormous a project to contemplate, so we cling to legacy codebases long past the point where their design has become outdated.

From the user’s perspective, this has perverse consequences. Your spreadsheet app is cluttered with features you, personally, will never have a need for. Your messaging app nags you to import contacts from another app that you don’t even use. Cybercriminals steal your personal information through a security hole in an update that you didn’t care about. Basically, three quarters of the engineering team behind any given product is engaged in making your life worse.

This awkward paradigm is dictated by the fact that software is expensive to develop. To be viable, an application needs many users, and each will have different needs. This leads to an upward spiral in cost and complexity, where increasing requirements require a larger engineering team, which can only be afforded by targeting an even wider user base.

What happens when software is no longer expensive to develop?

Coding Agents Enable Locally-Grown Software

AI coding agents are becoming capable of building and maintaining entire small applications – at negligible cost. Rather than targeting mass audiences, we can create software designed to meet the needs of a single user or team. Ironically, AI will allow software to become more artisanal. (Jason Crawford touches on a similar theme in his excellent recent post, In Defense of Slop.)

A personalized solution can include just the features needed by its small audience, making it tractable to vibe-code. (Imagine a simple AI-coded task manager built around your personal organizational system.) This allows us to invert the spiral: just as complexity breeds complexity, simplicity breeds simplicity. There’s no big engineering team to coordinate, no complex codebase to maintain. If the code becomes messy over time, you can always throw it away and start over. You can ask for changes and get them immediately, without being buffered by intermediaries and quarterly planning processes.

To be sure, there are limits to how widely this approach can be applied given current AI capabilities. Coding agents struggle with unusual tasks; they may write insecure code; bespoke applications may create training challenges for new team members (though their simplicity should help). But many detractors fail to recognize how quickly these limits are receding. They also fail to appreciate that new approaches to software development, enabled by coding agents, render some traditional concerns obsolete. For instance, they will point out that if you don’t review AI-generated code, you won’t know how it works. But that’s fine; the AI can analyze it on demand. Over time, multiple rounds of change may lead to unmaintainable code; you can just tell the AI to rewrite the application from scratch. Many objections to vibe coding, used in a way that plays to its strengths, are akin to an engineer from 1880 predicting that a factory with hundreds of electric motors would be as much of a maintenance nightmare as hundreds of steam engines would have been.

(It’s worth noting that something like half of all software engineers are currently employed building internal applications for small organizations and departments2. Vibe coding could rapidly transform this kind of work.)

Call this “locally grown software”. It won’t have the rich feature sets we’re accustomed to, but any missing features can be added on demand. And compared to factory-farmed software, the local stuff will be simple, quick to load, and rarely offer unpleasant surprises.

To be clear, this will (at first) apply only to some types of software. Professional engineers will still have an important role to play.

Steam Power Thrived In the Electric Age

In 1880, shortly before factories began adopting electric motors, steam power employed in manufacturing in the US had a total capacity of around 2 million horsepower. In 1930, after the transition was largely complete, electricity generation alone used twelve times this amount of steam power. Electrification did not eliminate steam; it simply moved it to central generator stations3.

By the same token, the new era of locally-grown software will not (for now) eliminate the need for professional engineers. Vibe-coded apps rely on extensive functionality provided by web browsers like Chrome, Safari, or Firefox. They store data in scalable backend services managed by providers like Amazon, Microsoft, or Google. These trustworthy, scalable, performant systems provide guardrails that reduce the risks of using janky vibe-coded software. For instance, you don’t need to worry about a buggy app wiping your hard disk, because your browser doesn’t allow the app to affect anything outside of its own web page.

There are many other categories of software that will continue to be developed by professional teams and designed for a wide audience. Web apps are built on foundational software called a “framework”; designing a framework requires sophisticated judgement. Some applications, like Photoshop, are too complex to be handed over to AI agents at their current level capability. The list goes on. AI coding agents will affect the way these systems are built, too, but they are nowhere near to handling the job autonomously.

Conclusion

As AI becomes increasingly capable, it will be worthwhile to retool practices around AI’s strengths and weaknesses. Unsurprisingly, software development is one of the first industries in which this transformation is playing out. As is often the case with disruptive technologies, vibe coding’s weakness (it’s not suited for large, complex projects) is also a powerful strength (it enables a transition to simple, bespoke software). Coding agents struggle with the sprawling codebases and idiosyncratic design choices typical of traditional software development, but this will not limit their usefulness nearly as much as some people imagine4. Engineers will find their role changing rapidly.

Software development is not the only domain in which economies of scale have led to one-size-fits-all solutions that don’t really fit anyone very well, and AI may soon transform these fields as well. AI is not (yet) capable of writing a high-quality newsletter, but it can create a custom weekly briefing whose tight personalization might more than compensate for bland writing. If you’re learning a new subject, AI can’t yet reproduce the polish of a professionally designed textbook, but it can give you a clear explanation of whatever specific concept you’re stuck on. Many fields are ripe for a similar shift from mass-market to bespoke.

Electric motors didn’t revolutionize manufacturing by doing the job of a steam engine. They did it by enabling a new approach to machine power that eliminated the need for shaft-and-belt systems and multi-story factories. AI is going to revolutionize industries, not by doing traditional jobs in traditional ways, but by enabling new, often more personalized, approaches.

Thanks to Abi Olvera and Taren Stinebrickner-Kauffman for suggestions, feedback, and images.

Long belts or shafts suffered from problems with friction, misalignment, and belts that would sag or “whip”.

Per Claude, other factors also contributed to the multi-story layout: urban land costs, building techniques of the era, and the fact that many early factories evolved from water-powered mills (which were multi-story because machinery needed to be close to the water wheel).

Most of the rest work in mid-tier projects; only a small fraction of programmers work on web-scale systems. This is based on research by Claude Opus 4.5 and Gemini 3 Pro, which independently arrived at similar figures, and is consistent with my own understanding of the industry.

The 2M HP is for manufacturing alone; the 24M HP figure is for all uses of electricity. Both figures were researched using Google AI Mode, and should not be relied on. Also during this period, reciprocating steam engines were largely replaced by steam turbines, which are more efficient; I’m lumping both under “steam power”.

Even within large projects, practices will shift toward increased use of software that’s suitable for vibe coding: isolated libraries, internal utilities, test harnesses, observability tools, and so forth.

This is great -- but as I think about the domain I mostly work in -- web sites for e-commerce -- it's unclear if the analogy holds. A company that's trying to sell things still has just one web site, showing its products. (Or, in the case of a marketplace, its sellers' products.) What would it even mean to be bespoke, simple software in that context?

The current trends in e-commerce seem to be "agentic" -- e.g., https://blog.google/innovation-and-ai/infrastructure-and-cloud/google-cloud/nrf-2026/ . Instead of searching a web site to find shoes, you interact with an AI agent that more-or-less simulates a sales person. "I'm looking for sneakers similar to the ones I'm wearing now, but wider and a little bit flashier", or whatever.

But that's not custom software, in the sense that this article postulates. So what would be?

Consistently my favorite substack read. One issue with custom software is the myriad of bugs and forgotten use cases. I wonder if we get an explosion of stable, secure open source instead. Maybe AI mostly just glues existing packages together.