Presenting the Case That the Future Will Be Unrecognizable

We should prepare for the possibility of profound change

Leaders in the AI world are not shy about hyping the technology’s potential.

“AI is probably the most important thing humanity has ever worked on. I think of it as something more profound than electricity or fire.” – Sundar Pichai (Google CEO)

“[T]he 2030s are likely going to be wildly different from any time that has come before.” – Sam Altman (OpenAI CEO, from “The Intelligence Age”)

“It’s quite conceivable that humanity is just a passing phase in the evolution of intelligence.” – Geoffrey Hinton (”Godfather of AI,” 2024 Nobel laureate)

“I think that most people are underestimating just how radical the upside of AI could be, just as I think most people are underestimating how bad the risks could be.” – Dario Amodei (CEO, Anthropic)

What if we took these statements seriously?

I spend a lot of time in this blog arguing that AI’s near-term impact is overestimated, to the point where some people think of me as an AI skeptic. I think that predictions of massive change in the next few years are unrealistic. But as the saying goes, we tend to overestimate the effect of a technology in the short run, and underestimate it in the long run1. Today, I’m going to address the flip side of the coin, and present a case that the long-term effect of AI could be very large indeed.

I think it’s entirely possible that the leaders I quoted above are right about the scale of transformation we should expect from AI. If they are, then we are heading for changes so profound that they may very well lead to what I’ll call the Unrecognizable Age.

AI Is Moving Toward a Critical Threshold

History is littered with predictions that everything is about to change, and of course, they’re usually wrong. But sometimes everything really does change. In the billions of years of life on Earth, no species ever created a technological civilization – until Homo Sapiens. Across the umpteen millennia since our species evolved into its current form, we were always limited to muscle power2 – until the Industrial Revolution.

Dramatic changes are often the result of a threshold being crossed. A virus that infects an average of 0.9 victims quickly fizzles out; a virus that infects 1.1 victims can sweep through an entire population. Homo Sapiens became a big deal when we became intelligent enough to advance through culture rather than genetic evolution. Early agriculture didn’t have much impact until it enabled a tribe to obtain more food than they could by hunting and gathering.

Here’s a threshold AI may be approaching: it may soon be the first technology to be more adaptable than we are. It’s not there yet, but you can see it coming – the range of problems to which early adopters are successfully applying AI is simply exploding. Past inventions had limited impact, because they could only be adapted to some uses. But AI may (eventually) adapt itself to any task. When technology makes one job obsolete, people move into another – one that hasn’t been automated yet. But at some point, AI could be retraining faster than people can.

When that happens, it could well lead to a constellation of technologies powerful enough to usher in the Unrecognizable Age. This constellation would rest on three pillars:

AI systems that are capable of doing pretty much anything that people can do, at the same or higher speed and quality – including “soft” skills such as judgement, taste, and style.

Robots that clear a similar bar (or nearly so) for physical tasks.

Advances in material science, manufacturing techniques, and related technologies that expand what we can accomplish in the physical world while reducing our footprint on the environment.

I’ll call this Richter 10.0 AI, because it would register a 10.0 on Nate Silver’s Technological Richter Scale – above agriculture, the Industrial Revolution, and the atomic bomb. The only previous event to rate a 10 is the emergence of Homo Sapiens as the dominant species on Earth; this level of AI could be equally impactful.

I would not be surprised to see AI to cross the critical threshold – becoming more flexible and adaptable than human beings – in a matter of decades3, and the Unrecognizable Age to follow fairly soon thereafter.

Why The Tipping Point Seems Near

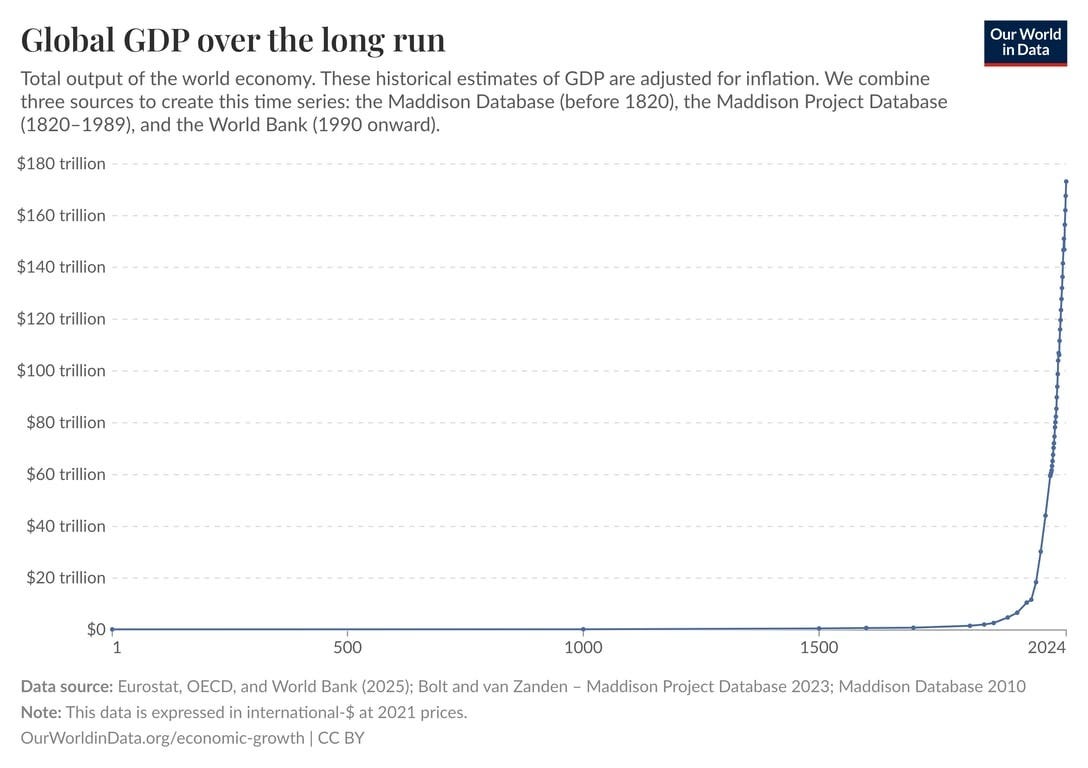

We’re at the right point in history for everything to change. Here’s a graph of global economic output over the last two millennia:

Source: https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/global-gdp-over-the-long-run

Economic growth has been hyper-exponential – the percentage rate of change has been increasing. As a result, the surplus available that isn’t needed for basic needs is far larger than at any point in history. Much of this surplus winds up being invested to drive technological advancement – hence the current astonishing level of investment in AI data centers. The coming decades sure look like a good candidate for being the point in history when we’ll have the resources to push AI over the threshold.

The tech-industrial complex has tasted blood. A quorum of leadership and staff in Silicon Valley is convinced that AI is a multi-trillion-dollar opportunity (or more!) – and is unwilling to risk being left behind. As a result, the vast intellectual and financial might of the tech industry are being brought to bear. On current forecasts, within a few years the AI industry may be spending more (adjusted for inflation!) on data center construction than the US did to fight World War II4. Annual spending is already about 15 times the peak of the Apollo program, and 25 times larger than the Manhattan project (though AI spending is not focused on a single effort in the way those projects were). Even if current approaches stall out, there are already multi-billion-dollar efforts to find alternatives5. The techniques underlying Moore’s Law have hit a wall many times over the years; repeatedly, the industry found new paths forward. It seems likely that the AI industry now has similar momentum.

There is speculation that AI may experience a “bubble pop”. This could happen, and put a dent in the level of investment. But if so, it seems likely to be similar to the collapse of the dot-com bubble – which was only a minor setback to the advance of the web. Google and Amazon weathered the storm just fine.

Progress in AI over the last 50 years suggests we are closer to the finish line than the starting line. Consider recent history in 25-year increments:

In 1950, computers were built from vacuum tubes, and couldn’t play a decent game of checkers.

In 1975, computers had only recently transitioned from individual transistors to integrated circuits6. The forefront of AI included rule-based systems that were beginning to demonstrate capabilities in specific areas of medical diagnosis... but did not achieve real-world use.

In 2000, the cutting edge was shifting from specialized supercomputers to general-purpose CPU chips like Intel’s Pentium. IBM’s Deep Blue had recently beaten the world chess champion, speech recognition was just starting to become practical, and early algorithmic targeting systems like Google’s PageRank were emerging.

In 2025, AI has shifted from general-purpose CPUs to specialized multi-chip GPU modules, soon to be deployed in clusters that will consume the output of entire nuclear power plants. AIs are able to engage in erudite conversation on literally any subject, are surpassing elite human performance at math and coding competitions, and are generally leaping from strength to strength in ways I don’t need to belabor here.

Look back at 1975, and jump again to 2025. It seems difficult to claim that another 50 years won’t lead to full on, science-fiction-grade, indistinguishable-from-magic levels of AI. (Even without taking into account that AI progress has been accelerating!) Many people in the AI world think this will take much less than 50 years, and I think that’s quite plausible, but even if it’s 50 years away that’s still an extraordinary prospect.

“I set the date for the Singularity—representing a profound and disruptive transformation in human capability—as 2045. The nonbiological intelligence created in that year will be one billion times more powerful than all human intelligence today.” – Ray Kurzweil (Google futurist, writing in 2005)

This caliber of AI, in turn, should help accelerate progress in fields like material science, robotics, and manufacturing, rounding out the three pillars of Richter 10.0 AI.

But What About [Insert Reason AI Won’t Be a Big Deal]?

There are, of course, objections to the idea that AI will transform the world. Regulations and job concerns will hold back deployment. If AI automates one job, the economy will shift to some other bottleneck. The things that are holding back global progress have more to do with politics and bad incentives than a shortage of intelligence. And so forth.

All of these things are true, and they will slow things down for a while – as I’ve often argued. But the key phrase is “for a while”. Eventually, if advanced AI exists in the world (and is not somehow under tight control), that will open up many new possibilities for getting around these barriers. Here’s a scenario I’ve thrown together to illustrate how that might happen.

In 2055, some company or nation launches a trillion-dollar initiative to deploy heavy industry in the asteroid belt, leveraging 30 years of (AI-assisted) advances in material science and other foundational technologies. Ten thousand advanced robots, plus equally sophisticated supporting equipment, land on Ceres and set up mining and manufacturing operations. Each year, they manufacture enough to double their equipment base. By the end of the first year, the ten thousand robots have built ten thousand more. By the end of the second year, twenty thousand robots have become forty thousand. In 2065, ten rounds of doubling have brought the total to 10 million, and advances in material science and fusion power (plus economies of scale) cut the doubling time in half – one robot can now produce another robot and its share of equipment in six months. By 2075, there are ten trillion robots honeycombing the (now noticeably depleted) 587-mile-wide asteroid.

All along, this robot army has been constructing the industrial base to reproduce itself... while also constructing data centers alongside the factories. In addition to ten trillion robots, Ceres now houses ten trillion disembodied digital minds, all engaged in advancing the frontiers of science and technology (and supported by a trillion robots diverted to serve as lab technicians). In round numbers, this exceeds human R&D efforts by a factor of one million. Things begin to progress even more rapidly.

In this scenario, permitting requirements and environmental impact review won’t apply. No one will be losing their jobs, because no one is employed in developing an industrial base on Ceres. A self-sufficient robot economy, with vast intellectual resources and no internal politics, should be able to work around bottlenecks as they arise.

In reality, of course, something much more complicated and clever and stupid will happen. My point is simply that once AI crosses some threshold of adaptability and independence, there will be paths around the traditional barriers to change. And then things will really start to get weird.

Implications of Richter 10.0 AI

Many of the bedrock assumptions underlie economics, politics, and our fundamental intuitions would be invalidated by Richter 10.0 AI:

Our resources are limited to those available on Earth. Robots will have a far easier time exploring the solar system than delicate, precious human beings.

We can scale capital but not labor. Historically, while we can always build more factories, the labor supply grows slowly (if at all). When AIs and robots supply labor, labor becomes scalable.

Skills are expensive to replicate. People require years of training to acquire advanced skills; AIs can be duplicated in a matter of seconds.

The rate of change is limited by the speed at which people can adapt. People need retraining. They have specific preferences and aptitudes, so can’t be arbitrarily reallocated from one role to another. They can’t (or shouldn’t) be hired and fired at a whim. AIs can be repurposed on demand.

Most economic output is devoted to meeting people’s needs, not R&D. Trillions of robots can enable a vast economy without having to support trillions of workers in a comfortable lifestyle.

In the Ceres scenario, humanity’s collective R&D efforts increase by a factor of one million. This could drive an inconceivable pace of advances across every field, which could be instantly deployed throughout the economy – or, at least, the automated portion of the economy, which will be literally astronomical in scale. And all of this would constantly feed back on itself. The resulting world could be unrecognizable indeed.

Of course, this assumes that we don’t stop the train. Some people propose that the world should collectively choose to not develop advanced AI. Or a major war or other global disaster could shatter the delicate supply chain for the cutting-edge chips that are powering AI progress. But if we don’t wind up stopping, big things may be in store. The prospect is simultaneously thrilling and terrifying.

Looking Into the Unknown

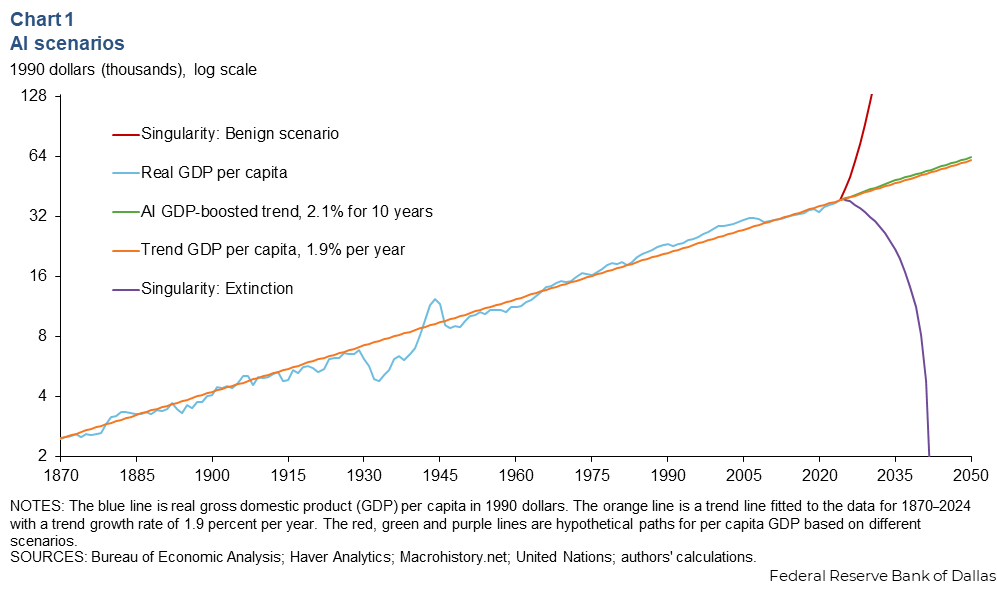

The Unrecognizable Age might go very very well, or very very badly. The following chart shows potential scenarios for future GDP growth, including business as usual, a “benign singularity”, and an AI extinction scenario. What fringe organization published this wild speculation? The Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas.

If AI indeed “goes big”, the future might hold a galactic utopia, full of wonders beyond our imagining. Or it might be sterile, an orderly domain of joyless machines, perfectly optimized for... well, who knows what, but with no one alive to appreciate it, perhaps it wouldn’t matter.

Other scenarios are also possible, but in many of them, the changes would be profound. With trillions of AI scientists and technicians pushing forward in every field, it is difficult to place a limit on the possibilities. Perhaps the new reality will feel natural as we live through the changes day by day. But from my present-day vantage point, if I try to stare at this future for too long I go mindblind. The possibilities are too vast, the questions too unanswerable.

None of this is imminent. I discount claims that AI will revolutionize the world in the next few years. But I think there is a strong case that we will create Richter 10.0 AI within 50 years – conceivably much, much less. It’s time that we take seriously the possibility of an Unrecognizable Age. There are plenty of questions to be explored. We can promote beneficial applications of AI, and look for ways to minimize risks. We should certainly monitor progress, and build the institutional capacity to navigate change. In my work at the Golden Gate Institute for AI (including this blog), I’m trying to do my part.

No one knows exactly how to prepare the world for AI. But together, we can try to plot our course toward the light, even if we can’t stare directly into it.

Thanks to Abi Olvera, Adam Pisoni, Jonathan Matus, Kristen Hamilton, Russ Heddleston, Taren Stinebrickner-Kauffman, Timothy Lee, and Tony Asdourian for suggestions and feedback.

Further reading on the implications of advanced AI:

It turns out that this adage has a name – Amara’s Law.

Well, muscle power plus a bit of wind power.

By saying “decades”, rather than “a decade”, I do qualify as a skeptic in significant segments of the AI community!

Estimates for US peak annual spending on World War II, in 2025 dollars: $1.15 trillion (Gemini 3), 1-1.2 trillion (Opus 4.5). AI capex estimates for 2025: $500 billion (Gemini 3), $450-500 billion (Opus 4.5; includes non-AI data centers). AI capex is projected to continue growing rapidly in the coming years, and could easily exceed the WWII figure before the end of the decade. For instance, a McKinsey report estimated $5.2 trillion in capital expenditures on AI alone (excluding non-AI data centers) between 2025 and 2030, which would entail well over $1 trillion / year in some years.

For instance, prominent AI researcher Ilya Sutskever’s new company, Safe Superintelligence, Inc. has already raised three billion dollars and. In a recent interview, Sutskever indicated that the company is using that funding strictly for research, and that “we are entering the age of research”, with many new paths being explored to unlock further AI capabilities.

I’m simplifying here; the transition to integrated circuits was actually centered in the late 1960s.

One thing about your robot asteroid example is that attainment of AGI is not even the necessity there. There are other developments required of course such as the ability of efficiently creating a new robot using other robots (not to mention the physical resources that are needed for this) and the ability to error-correct without human intervention. It is is entirely possible that all this happens without reaching human level abilities for adaptations and generalizations.

Hard to argue against what *may* happen, but there's a few things I found unconvincing here:

- If you click through the GDP graph and look at it in log scale, you see that it's not smoothly hyperexponential, but rather it looks piecewise exponential. Since 1950 the graph "just" looks like a straight exponential (Link: https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/global-gdp-over-the-long-run?yScale=log&time=1900..latest). This still has lots of potential to go wild, but there's a difference between "GDP eventually surpasses any bound" and "GDP surpasses any bound by 2050".

- Adaptability is an important benchmark, but it doesn't seem to be the way AI is improving. At least in my experience, when AI cannot do a given task, one can't do much retraining to help it out, but has to wait for newer models. E.g.: My dad wanted to try transcribing a lot of handwritten documents, GPT-4o produced utter gibberish (random letters), but now Gemini 3 can do it accurately enough to be useful. This doesn't seem like an improvement in adaptability, but in overall ability? Which is nice, but also suggests that there might be bottlenecks once data becomes scarce or unreliable (e.g. medical tasks).

- The section on spending and on computer technology in general is about the effort put into this, not the outcomes. The outcomes that are there are benchmark-y: we have learned a lot about chess, but unclear how much about human intelligence. Similarly for competitions versus practical problems. "Erudite conversation on literally any subject" is notoriously hard to test for actual value, and the smart people I know seem pretty divided into two extreme camps in their usage of AI.

I'm not even an AI skeptic, more of a no-idea-what's-gonna-happen-er, but this is the kind of stuff I'd like to see better addressed. For example, there was a brouhaha a while ago about "LLMs passing the Turing test", but when you actually read that paper, you found that the average conversation length was something like 4 sentences and the human test subjects were psychology undergrads who just wanted credits for participation and had no incentive to do well in the test. It would be interesting to get something more solid in this direction.